Author: Nirvani Bhawsar

Make-up can be an instrument for self-expression and liberation. Like the clothing industry, the cosmetic industry has a dark side too. In India’s mica belt, the land between the borders of Jharkhand and Bihar, the land sparkles as the sun rises. India accounts for 60% of the world’s mica production and the cosmetics industry is one of the largest consumers of mica. It is used to add shimmer to cosmetics such as lipstick, eye shadow, blush, etc. Children as young as five years old, equipped with hammers and shovels venture into dark endless tunnels to extract mica. Profits are made on the backs of children, who often do not know the name of the mineral in their hands. This area is a perfect example of a resource curse.

A land of child exploitation

According to The Centre for Research on Multinational Corporations (SOMO), one-fourth of the world’s mica comes from Jharkhand and Bihar. Approximately 22,000 children work in these illegal mines. The mica belt is one of the poorest regions in the country with high rates of illiteracy and unemployment. According to the Handbook of Statistics of Indian Economy, nearly 33.74% of Bihar’s population and 36.96% of Jharkhand’s population lives below the poverty line. This contributes to child labour in these areas.

Most mining activities in Jharkhand and Bihar are illegal. Since 1950, the number of legal mines in these areas has been constantly decreasing. After the Forest Conservation Act, 1980 the central government altogether stopped renewing mining licenses. This mushroomed illegal mining. According to the Indian Bureau of Mines, in 2014 there were only two legal mines in Bihar and no legal mines in Jharkhand.

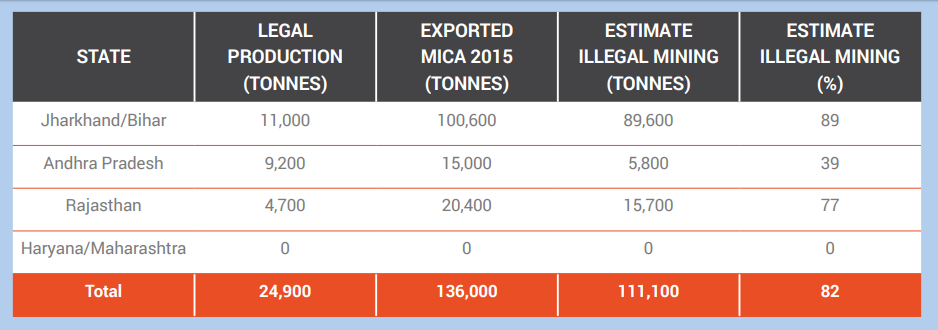

The above table illustrates the severity of illegal mining in such areas.

Since most mines are illegal, heavy machinery is often not used. This increases reliance on manual labour. Mica is mined using underground tunnels which are extremely small in size and children are considered perfect due to their size for mining in these small tunnels. Both these reasons make child labour lucrative for mining industries.

Effect on Children: Health and Education

Mica mining is one of the worst forms of child labour because of the hazardous conditions of the work. The biggest risk of working in such small mines is that they can collapse at any point putting children at risk of being buried alive. Such incidents often go unreported and the families of the children are given “blood money” to not report and continue mining. Children are exposed to silica dust which can lead to severe lung diseases. They are susceptible to bruised, skin infections, breaking bones, and heat strokes. Because of the health hazards of mica mining, families are forced to take loans from loan sharks for the medical treatment of their family members. This pushes them into debt traps and bondage – yet again leaving them with no choice but to work in these mines to repay loans. These loan sharks are generally merchants and managers of illegal mica mines, locally known as “mica mafias”.

The child is deprived of the Right to Education and made to work in mines for a meagre pay of a few rupees. According to the National Commission for Protection of Child Rights’ Survey on Education & Wellbeing of Children in MICA Mining Areas of Jharkhand & Bihar, 4,545 children between the age of 6 to 14 years in such areas of Jharkhand and Bihar are not attending school as they are employed in mica mines. In a vicious circle, when these children turn into adults, they are unable to find jobs due to lack of education and are left with no choice but to continue working in these mines.

Legal Framework

In India, the Child Labour (Prohibition and Regulation) Act of 1986 and the Mines Act of 1952 (as modified in 1983) prohibit child labour in mining. The Child Labour (Prohibition and Regulation) Act of 1986 prohibits children under the age of 14 years from working in underground mines, to cut/split mica, and work on processes involving exposure to free silica. Whereas, the Mines Act of 1952 (as modified in 1983) states that, “no person below eighteen years of age shall be allowed to be present in any part of a mine above ground where any operation connected with or incidental to any mining operation is being carried on”.

On the international front, India has ratified two core conventions on Worst Forms of Child Labour and on Minimum Ages: i) C138 – Minimum Age Convention, 1973 and ii) C182 – Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention, 1999 of the ILO with regard to child labour. While the C138 – Minimum Age Convention, 1973 provides that no hazardous work should be done by a child under the age of 18 (in case of India the minimum specified age is 14), the C182 – Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention, 1999, requires states to take immediate action against the worst form of child labour in their country.

Corporate Responsibility to Combat Child Labour in Mica Mining Industries

Awareness about child labour in supply chains has grown immensely in recent years due to the work done by various organizations, government and the media. This has increased the pressure on businesses to address and prevent such problems. Of significance is the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs, 2011) which takes into account responsibilities of businesses to respect human rights (including children’s rights). It mandates corporations to have policies in place to address issues such as child labour in the supply chain.

Many big corporations have acknowledged the presence of child labour in this industry and have taken steps to address the same. Companies such as Estée Lauder, L’Oréal, Clarins, Coty, Chanel, and Burt’s Bees have joined the Paris-based Responsible Mica Initiative (RMI). RMI in collaboration with these companies works to ameliorate child labour by tracing the supply chain back to the processors and mines which supply the mica. In addition to this, the member companies have adopted within their own supply chain, standards that encompass environmental, health, safety, legal, and fair labor practices, including a prohibition on the use of child labor.

When UK-based Lush cosmetics was tipped of the situation of child labour, they shifted to artificial mica. This ‘cut and run’ tactic was criticized by many experts as it worsens the situation by rendering such families unemployed. It does not recognize that big corporations are part of the problem and rather than severing themselves from the problem corporations should make conscious efforts to solve it. This can be done by improving traceability and accountability of the raw materials procured.

Efforts by Governments and NGOs: What is the Road Ahead?

Apart from consumer demands for ethical and cruelty-free products, governments are also providing incentives for companies to strive for a change. Governments are now demanding increased transparency from companies. For example, in Netherlands the Child Labor Due Diligence Act has been passed (date of entry into force is not yet decided) by the Dutch Senate which requires companies, including companies registered outside the Netherlands, selling goods or services to Dutch end-users (be it companies or individuals) to exercise due diligence to assess whether a “reasonable suspicion” exists that the services or goods to be supplied have come into existence using child labor. Violation can lead to hefty fines. The Act provides for Criminal liability as well.

In India, the Centre after analyzing the severity of the situation, implemented PENCIL scheme (Platform for Effective Enforcement of No Child Labour) in 23 districts of Bihar and 7 districts of Jharkhand to help in effective prohibition of child labour in these areas. It provides a platform to register online complaints regarding child labour and officers are appointed at district level to supervise reported cases. The rescued children are sent to centres where they receive education or vocational training. On regional level, Bachpan Bachao Andolan (BBA), an NGO set up by Nobel laureate Kailash Satyarthi in 1980 is addressing this issue and protecting children from child labour and trafficking. It has adopted Bal Mitra Gram (BMG) or Child Friendly Village (CFV), a development model where children themselves advocate for child rights and holistic development of their villages. This model seems to be working as until now 60 villages in the mica belt have been converted into CFV and 2,370 children have been admitted to school.

Education can cure this problem from the roots. Therefore, the government should increase the quality of educational facilities in these areas. There should be more incentives for to the children to attend school. Sustainable alternative income-generating possibilities for the families concerned in the mica mining area of Jharkhand/Bihar must also be developed, in order to combat child labour in these areas. Only such active and conscious steps by corporations, regional organizations and governments can ensure a life of dignity and respect for the children and their families of Jharkhand and Bihar trapped in mica mining.